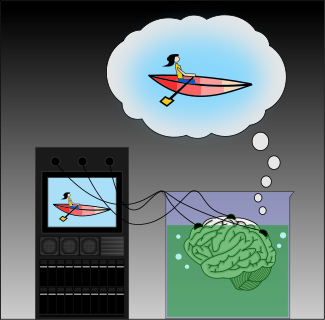

Think about the possibility that a human brain might be implanted in a vat connected with a computer Simulating the Fake Reality. The supercomputer would keep the brain alive and working while also allowing the creation of virtual stimulation and feeding them straight into the brain, making it believe that it is experiencing the real world. All of these inputs would be registered by the brain in the same way that typical human sensory experiences are because they are already understood as electrical signals. In this technique, the computer might build a whole imaginary environment that would appear entirely natural and accurate to the trapped brain connected to a computer. learn more

Contents

What is meant by Brain in a Vat(BIV)?

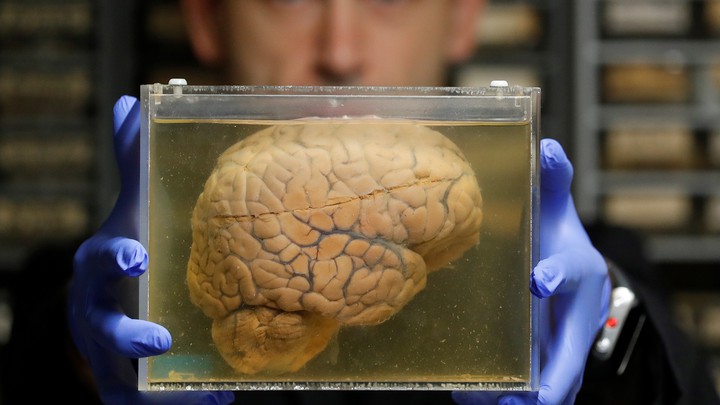

The brain in a vat(BIV) is a thought experiment scenario used in philosophy to draw out particular elements of human concepts of knowledge, reality, truth, mind, consciousness, and meaning. It is a current rendition of Gilbert Harman’s wicked demon thought experiment, which René Descartes first proposed. It describes a scenario in which a mad scientist, machine, or other entity removes a person’s brain from the body, suspends it in a vat of life-sustaining liquid, and connects its neurons to a supercomputer, which provides it with electrical impulses identical to those received by the brain typically. According to such stories, the computer would then be simulating reality (including appropriate responses to the brain’s output), and the “disembodied” brain would continue to have perfectly normal conscious experiences similar to those of a person with an embodied brain but without any connection to real-world objects or events.

In other words, the skeptical notion that one is a brain in a vat with consistently delusory experience is based on the Cartesian Evil Genius hypothesis, which states that one is a victim of a God-like deceiver who causes the continuous error. The skeptic claims that one cannot know that the brain-in-a-vat theory is untrue since if it were real, one’s experience would be identical to that of the skeptic. As a result, according to the skeptic, no statements regarding the external world are known (propositions that would be false if the vat hypothesis were true).

Based on semantic externalism, Hilary Putnam (1981) gave an apparent rebuttal of a variant of the brain-in-a-vat hypothesis. This is the belief that the meanings and truth conditions of one’s sentences and the contents of one’s intentional mental states are determined by the external, causal environment. This item is primarily concerned with examining Putnam’s ideas, which appear to demonstrate that one can know that one is not a brain in a vat.

Applications of Brain in a Vat

The most straightforward application of brain-in-a-vat scenarios is as a justification for philosophical skepticism and solipsism. The following is a simplified version: The brain in a vat sends and receives the same impulses as if in a skull. Because these are its only means of interacting with its environment, it is impossible to distinguish whether it is in a head or a vat from the perspective of that brain. However, in the first scenario, the majority of the person’s views may be correct, but if they believe they enjoy boating in the river, their beliefs are incorrect.

Since it is impossible to know whether one is a brain in a vat, it is also impossible to tell whether most of one’s beliefs are utterly incorrect. Moreover, since it is impossible to rule out the possibility of oneself being a brain in a vat in principle, there can be no good reason to believe any of the things one considers; a skeptical argument would argue that one cannot know them, which would raise concerns with the definition of learning. Other philosophers have used sensation and its relationship to meaning to question whether brains in vats are fooled, increasing broader problems about perception, metaphysics, and language philosophy.

The brain-in-a-vat is a modern take on the Sanatan-Hindu Maya illusion, Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, Zhuangzi’s “Zhuangzi imagined he was a butterfly,” and René Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy’s terrible demon. Many current philosophers feel that virtual reality, as a sort of brain in a vat, will significantly impact human autonomy. Another point of view is that virtual reality will not disrupt our cognitive structure or our connection to reality. On the contrary, virtual reality will provide us with more new ideas, insights, and perspectives on the world.

Arguments and Hypotheses

While the disembodied brain (brain in a vat) can be considered a helpful thought experiment, there are various philosophical disagreements about the thought experiment’s credibility. Suppose these disputes lead to the conclusion that the thought experiment is implausible. In that case, one possible outcome is that we are no closer to knowledge, truth, awareness, representation, or anything else than before the experiment. Most of the hypotheses and arguments have been explained below.

The Skeptical Hypotheses

The Cartesian skeptic proposes several logically plausible skeptical hypotheses for our consideration, such as the possibility that you are currently dreaming about reading an encyclopedia entry. The most radical Evil Genius concept is that you live in a universe with only you and a God-like Evil Genius bent on deception. Nothing physical exists in the Evil Genius realm, and the Evil Genius directly causes all your experiences. As a result, your experiences, which suggest an external universe of physical objects (including your body), lead to a series of erroneous ideas about your environment (such as that you are now sitting at a computer). As a result, some philosophers argue that the Evil Genius theory isn’t logically possible at all.

Materialists who believe that the mind is a sophisticated physical system reject that an Evil Genius world could exist because your mind could not exist in a matterless world, according to them. As a result, a modern skeptic will ask us to evaluate an updated skeptical hypothesis that is materialist. For example, consider the possibility that you are a floating brain in a vat of nutritional fluids. This brain is linked to a supercomputer, whose software generates electrical impulses that activate the brain in the same manner as regular brains are stimulated by perceiving external objects.

Does the skeptic pose a challenge after sketching this brain-in-a-vat hypothesis: can you rule out the option stated in the view? Are you aware that the idea is incorrect? The skeptic now makes the following argument. Select any target proposition P about the external world that you believe to be true:

- If you know that P, then you know that you are not a brain in a vat.

- You do not know that you are not a brain in a vat. So,

- You do not know that P is

Hypothesis

- backed by the principle that knowledge is closed under known entailment: (CL) For all S,α,β: If S knows that α and S know that α entails β, then S knows that β. Because you already know that P implies that you are not a brain in a vat (for example, let P = You are seated at a computer), you only know that P if you already know its implication: you are not a brain in a vat. The fact that your experiences do not allow you to distinguish between the hypothesis that you are not a brain in a vat (but rather a regular person) and the idea that you are a brain in a vat supports.

- The second hypothesis shows that, regardless of which theory was correct, your experience would be the same. So you’re oblivious that you’re not a brain in a vat.

The Biological Argument

According to The Biological Argument, The premise is that the brain in a vat(BIV) is not – and cannot be – biologically equivalent to that of an embodied brain is one argument against the BIV thought experiment (that is, a brain found in a person). Because the BIV is not displayed, its biochemistry differs from that of an embodied brain. The BIV, in other words, lacks connections between the body and the brain, making it neither neuroanatomically nor neurophysiologically similar to an embodied brain. If this is the case, we can’t assert that the BIV can have similar experiences to the embodied brain because the two brains aren’t identical. It may be argued, however, that the hypothetical machine could also be programmed to mimic those types of inputs.

Putnam’s argument is reconstructed in many ways.

Putnam’s argument has a flaw; even if his premises are correct, the only established truth is that when a brain in a vat declares, “I am a BIV,” it is false owing to the causal theory of reference. This isn’t proof that we’re not brains in vats; instead, it’s an argument based on externalist semantics. Several philosophers have attempted to recreate Putnam’s argument to address this problem. Some philosophers, such as Anthony L. Brueckner and Crispin Wright, have adopted disquotational ideas in their work. Others, like Ted A. Warfield, have focused on the concepts of self-knowledge and priori(distinguish types of knowledge, justification, or argument by relying on empirical evidence or experience. A priori knowledge is independent of experience).

The Contradictory Argument

One of the earliest but most influential reconstructions of Putnam’s transcendental argument was suggested by Anthony L. Brueckner. Brueckner’s reconstruction is as follows:

- Either I am a BIV (speaking vat-English) or a non-BIV (speaking English).

- If I am a BIV (speaking vat-English), then my utterances of ‘I am a BIV’ are actual if I have sense impressions of being a BIV.

- If I am a BIV (speaking vat-English), then I do not have sense impressions of being a BIV.

- If I am a BIV (speaking vat-English), then my utterances of ‘I am a BIV’ are false.

- If I am a non-BIV (speaking English), then my utterances of ‘I am a BIV’ are actual if I am a BIV.

- If I am a non-BIV (speaking English), then my utterances of ‘I am a BIV’ are false.

A key thing to note is that although these premises further define Putnam’s argument, it does not prove ‘I am not a BIV’ because although the premises do lay out the idea that ‘I am a BIV’ is false, it does not necessarily provide any basis on which false statement the speaker is making. There is no differentiation between a BIV making the statement versus a non-BIV making the statement. Therefore, Brueckner further strengthens his argument by adding a disquotational principle: “My utterances of ‘I am not a BIV’ are true if I am not a BIV.”

Externalist’s Argument

A second argument focuses on the inputs that enter the brain. The account of externalism, often known as ultra-externalism, is a popular term. The brain receives sensations from a machine in the BIV. The brain is embodied brain, on the other hand, receives stimuli through the body’s senses via touching, tasting, smelling, and so on, which receive input from the external environment.

This debate frequently leads to the conclusion that there is a distinction between what the BIV represents and what the embodied brain represents. Several philosophers, notably Uriah Kriegel, Colin McGinn, and Robert D. Rupert, have waded through this debate, which has repercussions for philosophy of mind discussions on (but not limited to) representation, consciousness, content, and embodied cognition.

Incoherence as a counter-argument

The philosopher Hilary Putnam proposed the third argument against BIV, which is based on a direction of incoherence. He tries to show this by using a transcendental argument, in which he tries to show that the thought experiment’s incoherence stems from the fact that it is self-refuting. To do so, Putnam first developed a link that he calls a “causal connection,” also known as a “causal constraint.” This relationship is further characterized by a theory of reference that states that implied authority cannot be assumed and that words are not always intrinsically linked to what they represent.

Semantic externalism was the name given to this theory of reference. Putnam illustrates this point further when he creates a scenario in which a monkey writes out Hamlet by accident; yet, this does not entail that the animal is referring to the play because the monkey has no knowledge of Hamlet and hence cannot link back to it. He then uses the “Twin Earth” example to show how two identical people, one on our planet and the other on another, might have the same mental state and thoughts while referring to two different objects.

When we think of cats, for example, the reference to our ideas is the cats we see here on Earth. However, our twins on twin earth would be referring to twin earth’s cats rather than our cats, although having identical sentiments. In light of this, he claims that a “pure” brain in a vat, one that has never been outside the simulation, could not even claim to be a brain in a vat. This is because the BIV can only refer to objects within the simulation when it says “brain” and “vat,” not to things outside the simulation with which it has no relationship.

Putnam calls this relationship a “causal connection,” also known as a “causal constraint.” As a result, everything it states is patently wrong. Alternatively, the assertion is also untrue if the speaker is not a BIV. As a result, he believes that the phrase “I’m a BIV” is consistently inaccurate and self-refuting. Since its publication, this argument has been extensively discussed in philosophical literature.

Even assuming Putnam’s reference theory, a brain “kidnapped,” placed in a vat, and subjected to a simulation on our planet could still refer to “real” brains and vats, and thus correctly say it is a brain in a vat, according to one counter-argument. However, in the philosophy of mind, language, and metaphysics, the idea that the “pure” BIV is erroneous and the reference theory that underpins it continues to have sway.

Conclusion

The brain-in-a-vat hypotheses are fundamental for developing skeptical arguments based on the Cartesian Evil Genius argument about the possibility of external world knowledge. Given semantic externalism and the premise that one has a priori knowledge of some vital semantic aspects of one’s language (or, alternately, a priori knowledge of the contents of one’s mental states), the BIV hypothesis may readily be refuted. Even if Putnam’s arguments do not exclude all variations of the brain-in-a-vat hypothesis, their success against the radical BIV hypothesis would be significant. These arguments also highlight a fresh perspective on the relationships between the mind, language, and the outside world.

Read more articles related to this article:

- Simulation Theory: All Possibilities of Reality are Artificial Simulation

- Existence: Is Your Reality a Complex Computer Simulation?

Sources

- Thompson, E., & Cosmelli, D. (2011). Brain in a vat or body in a world? Brainbound versus enactive views of experience. Philosophical topics, 163-180.

- Horgan, T., Tienson, J., & Graham, G. (2004). Phenomenal Intentionality and the Brain in a Vat. The externalist challenge, 2, 297.

- Black, T. (2002). A Moorean response to brain-in-a-vat skepticism. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 80(2), 148-163.

- Brueckner, A. (1992). If I am a brain in a vat, then I am not a brain in a vat. Mind, 101(401), 123-128.

- Gere, C. (2004). The brain in a vat (PDF). Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 35(2), 219-225.

- Harman, Gilbert 1973: Thought, Princeton/NJ, p.5

- Putnam, Hilary. “Brains in a Vat” (PDF).

- Klein, Peter (2 June 2015). “Skepticism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Bouwsma, O.K. (1949). “Descartes’ Evil Genius” (PDF). The Philosophical Review. 58 (2): 149–151. doi:10.2307/2181388. JSTOR 2181388 – via JSTOR.

- Cogburn, Jon; Silcox, Mark (2014). “Against Brain-in-a-Vatism: On the Value of Virtual Reality.” Philosophy & Technology. 27 (4): 561–579. doi:10.1007/s13347-013-0137-4. ISSN 2210-5433. S2CID 143774123.

FACT CHECK: We strive for accuracy and fairness. But if you see something that doesn’t look right, please Contact us.

DISCLOSURE: This Article may contain affiliate links and Sponsored ads, to know more please read our Privacy Policy.

Stay Updated: Follow our WhatsApp Channel and Telegram Channel.

Please comment with your views!