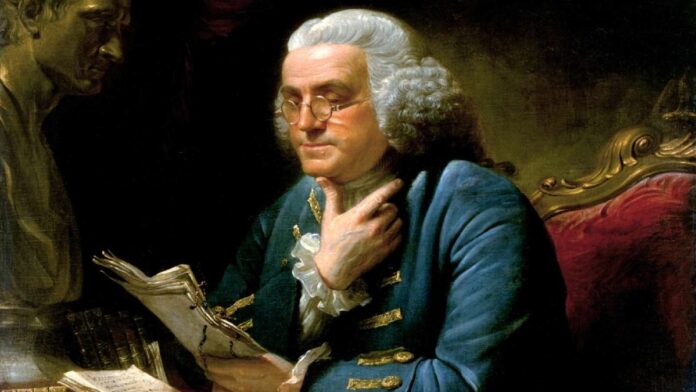

Benjamin Franklin was a multi-talented American inventor, civic activist, statesman, soldier, and diplomat. He was also one of the most influential United States Founding Fathers, serving as both a spokesperson and a model for the national character of future generations. For his studies and beliefs on electricity, he was a crucial player in the American Enlightenment and the history of physics as a scientist. His innovations include the lightning rod, bifocals, the Franklin stove, a carriage odometer, and the glass armonica’. He spent most of his life on the advancement of his people, leaving an indelible impression on the fledgling nation. Know more about Benjamin Franklin, a Brilliant Inventor, Statesman, and Scientist.

Contents

The early life of Benjamin Franklin

Born

Benjamin was born on January 17, 1706, in Boston, Massachusetts. He was the tenth of seventeen children born to a father who manufactured soap and candles, one of the lowest of the artisan industries. In an era when the firstborn son was favored, Benjamin was, as he pointed out in his Autobiography, “the youngest son of the youngest Son for five Generations back.”

Education

He acquired his initial schooling at Boston Latin School. He learned to read at a young age and spent one year in grammar school and another with a private teacher. Still, his formal education stopped at the age of ten, and he dropped out of school due to his family’s financial difficulties and maintained his education via enthusiastic reading. He was apprenticed to his older brother James, a printer, when he was twelve years old, and he learned the printing art from him. Benjamin had always desired independence and disliked being told what to do, so when he was seventeen, he ran to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1728, he founded his own printing house with Hugh Meredith. Between 1718 and 1723, he mastered the printer’s profession, which he was proud of till the end of his life. During the same time, he read voraciously and learned to write efficiently.

His initial enthusiasm was for poetry, but he abandoned it after being dissatisfied with the quality of his work. Young Benjamin came across a volume of The Spectator that contained Joseph Addison and Sir Richard Steele’s famous periodical pieces, which had been published in England from 1711 to 1712, and saw it as a way to improve his writings. He read the Spectator articles several times, copied and recopied them, and then attempted to recollect them from memory. He even converted them into poetry before returning to prose.

Job and Carrier

In 1721, James Franklin, his older brother, established the New England Courant, a weekly newspaper to which readers were welcome to contribute. Benjamin, now 16, read and maybe typed these contributions and concluded that he could do it. So, in 1722, he published 14 articles titled “Silence Dogood,” in which he mocked everything from funeral eulogies to Harvard College students. It was a remarkable effort for someone so young, and Benjamin took “exquisite Pleasure” because his brother and others were convinced that only an educated and cunning wit could have written these pieces.

Late in 1722, James Franklin Benjamin’s older brother fell in trouble with the provincial authorities and was barred from printing or publishing the Courant. To keep the business running, he released his younger brother from his original apprenticeship and appointed him as the paper’s nominal publisher. New indentures were drafted, but they were not made public. After a heated argument, Benjamin discreetly departed home, confident that James would not “go to law” and expose the ruse he had prepared.

After failing to find work in New York City, Benjamin moved to Quaker-dominated Philadelphia, which was much more open and religiously tolerant than Puritan Boston. The portrayal of his arrival on a Sunday morning, tired and hungry, is one of the most unforgettable sequences in the Autobiography. When he came upon a bakery, he asked for three pence’s worth of bread and received “three excellent Puffy Rolls.” He walked through the market with puffy rolls to the Reid family’s doorstep, where his future wife, Deborah, was standing. Deborah looked at him and realized, “I’ve made the weirdest appearance ever,“ as she certainly did.

He was rooming at the Reads’ and working as a printer a few weeks later. By the spring of 1724, he was enjoying the company of other young men who liked to read, and the governor of Pennsylvania, Sir William Keith, was encouraging him to start his own business. Benjamin returned to Boston at Keith’s advice to obtain the necessary funds. However, his father thought he was too young for such an enterprise, so Keith offered to foot the expense and arranged Benjamin’s travel to England to pick his type and build links with London stationers and bookstores.

Benjamin exchanged “some vows” regarding marriage with Deborah Read and departed for London in November 1724 with James Ralph. Barely over a year after landing in Philadelphia, he realized Governor Keith had not delivered the letters of credit and introduction he had promised.

Benjamin rapidly found work in his trade in London and was able to lend money to Ralph, who was attempting to establish himself as a writer. The two young men liked the theatre and the city’s other attractions, including ladies. Benjamin composed A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain (1725) while in London, prompted by his having set type for William Wollaston’s moral book, The Religion of Nature Delineated. In his essay, Benjamin argued that humans lack true freedom of choice and are not morally responsible for their actions. This was an excellent reason for his self-indulgent behavior in London and his ignoring Deborah, to whom he had only written once. He later disowned the leaflet, burning all but one of the copies he still had.

By 1726, Benjamin had become tired of London. He pondered becoming an itinerant swimming instructor, but when Thomas Denham, a Quaker merchant, offered him a position in his Philadelphia store with the potential of large commissions in the West Indian trade, he decided to return home.

Benjamin Franklin’s accomplishments and inventions

Denham died just a few months after Benjamin entered his shop. The young guy, now 20, returned to the printing trade and established a company with a buddy in 1728. He borrowed money two years later to become a sole proprietor.

His personal life was exceedingly difficult at the time. Deborah Read married, but her husband abandoned her and went missing. Benjamin’s first matching venture failed because he demanded a dowry of £100 to pay off his business debt. A solid sexual urge drove him to “low women,” and he felt compelled to marry. His love for Deborah was revived on September 1, 1730, and he married her.

Deborah would have been the only woman in Philadelphia at the time, as Benjamin had brought up a son, William, in marriage, William’s mother never recognized. Franklin’s common-law marriage lasted until Deborah died in 1774. They had a son, Frankie, who did not survive for more than four years, and a daughter, Sarah, who survived. William was raised at home and did not treat Deborah well.

Then the first coup by Benjamin and his companions was to obtain the printing of Pennsylvania paper currency. Benjamin assisted in founding this enterprise by producing a modest inquiry into the nature and necessity of paper currency in 1729. He eventually became the public printer of New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland. Other profitable endeavors were the Pennsylvania Gazette, which Benjamin began publishing in 1729, widely regarded as one of the best colonial newspapers, and Poor Richard’s Almanac issued annually from 1732 to 1757.

Benjamin excelled despite some setbacks. He made enough money to lend interest and invest in rental properties in Philadelphia and other coastal towns. In addition, he had franchises or partnerships with printers in the Carolinas, New York, and the British West Indies. As a result, he had become one of the wealthiest colonists in the northern region of the North American continent by the late 1740s.

As he made money, he devised several social improvement schemes. In 1727, he founded the Junto, or Leather Apron Club, to debate moral, political, and natural philosophy issues and share commercial skills. The desire of Junto members for improved access to literature led to the formation of the Library Company of Philadelphia in 1731.

Benjamin advocated a paid city watch, or police force, through the Junto. A paper read in front of the same gathering led to a volunteer fire department formation. In 1743, he sought an intercolonial Junto, which resulted in the creation of the American Philosophical Society. In 1749, he wrote Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pennsylvania; in 1751, he created the Academy of Philadelphia, which expanded to become the University of Pennsylvania. He also became an avid Freemason, promoting their “enlightened” causes.

Although he was still a craftsman, he was gaining political clout. In 1736, he was appointed clerk of the Pennsylvania legislature, and in 1737, he was appointed postmaster of Philadelphia. Before 1748, however, his most notable political contribution was creating a militia to defend the colony against a possible invasion by the French and Spaniards, whose privateers were operating in the Delaware River.

At 42, Benjamin had amassed enough riches to retire from active business in 1748. So he removed his leather apron and assumed the status of gentleman, a unique position in the 18th century. But, because no busy artisan could be a gentleman, Benjamin never worked as a printer again; instead, he became a silent partner in the printing firm of Benjamin and Hall, making an average profit of almost £600 per year for the next 18 years.

He declared his new position as a gentleman by having his portrait drawn in a velvet coat and a brown wig; he also bought a coat of arms and several enslaved people and relocated to a more enormous and more spacious mansion in “a more quiet part of Town.” But, most importantly, as a gentleman and “master of his own time,” he chose to engage in what he called “Philosophical Studies and Amusements.”

Electricity

Electricity was one of these strange amusements in the 1740s. An electrical machine delivered to the Library Company by one of Benjamin’s English correspondents introduced it to Philadelphians. Benjamin and three of his pals began investigating electrical occurrences in the winter of 1746 to 1747. Benjamin’s thoughts and attempts were reported piecemeal to Peter Collinson, his Quaker correspondent in London. Benjamin presented his findings cautiously since he didn’t know what European experts had already uncovered. Collinson published Benjamin’s works in an 86-page book titled Experiments and Observations on Electricity in 1751. The book was published in five English editions, three in French and one each in Italian and German in the 18th century.

Benjamin’s fame increased. The experiment he proposed to prove the identity of lightning and electricity was supposedly initially carried out in France before he tried the easier but riskier method of flying a kite in a rainstorm. His other discoveries, on the other hand, were novel. First, he distinguished between insulators and conductors. He created a battery that could store electrical charges. Finally, he developed new English words for emerging electricity science, including conductor, charge, discharge, condense, armature, and electrify.

He demonstrated that electricity was a single “fluid” having positive and negative or plus and minus charges, rather than two types of fluids, as was previously supposed. And he established that plus and minus charges, or states of electrification of bodies, had to occur in precisely equal amounts—a critical scientific theory known today as the law of charge conservation.

Benjamin began his research into electricity and was the first to establish the theory of charge conservation. He also performed his famous kite experiment, in which he flew a kite with the wire linked to a key while it was raining. He also discovered that laboratory-produced static electricity was akin to a previously inexplicable and scary nature occurrence as a result of this investigation.

Wave Theory of Light

In 18th-century experiments performed by other scientists, Benjamin was one of very few scientists who supported Christiaan Huygens’ wave theory of light. Nevertheless, Huygens’ approach proved to be true after experiments performed by other scientists.

Meteorology

Benjamin also observed wind behavior and discovered that storms did not always travel in the direction of the prevailing wind. This concept became very important to meteorology.

Heat Conductivity

Benjamin also conducted experiments on the nonconduction of ice, which garnered a great deal of acceptance from other famous scientists, including Michael Faraday.

Benjamin Franklin in Public Service

Despite the success of his electrical experiments, Benjamin did not consider science as vital as a civic duty. Nevertheless, as a leisured gentleman, he quickly rose through the ranks of more powerful public offices. He was elected to the Philadelphia City Council in 1748, a justice of the peace in 1749, and a city alderman and member of the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1751.

However, he aspired to be a part of a wider arena, the British Empire, which he saw as “the greatest Political Structure Human Wisdom has ever yet created.” In 1753, Benjamin was appointed as deputy postmaster general, with the responsibility of mail in all of the northern colonies.

Following that, he began to consider intercolonial issues. As a result, the Albany Congress, which assembled at the start of the French and Indian War and included representatives from the Iroquois Confederacy, endorsed his “Plan of Union” for the colonies in 1754. The proposal called for forming a general council comprised of delegates from the various colonies to prepare a joint defense against the French.

However, neither the colonial legislatures nor the king’s counselors were prepared for such a union, and the concept was abandoned. However, Benjamin had been acquainted with significant imperial officials, and his desire to rise through the imperial hierarchy had been piqued.

In 1757, he traveled to England as the Pennsylvania Assembly’s agent to persuade the Penn family, the owners under the colony’s charter, to enable the colonial legislature to tax their ungranted properties. However, Benjamin and some of his assembly friends had a greater goal: convincing the British government to depose the Penn family as proprietors of Pennsylvania and establish the colony as a royal province.

Except for a two-year visit to Philadelphia from 1762 to 1764, Benjamin spent the next 18 years in London, most of the time in the apartment of Margaret Stevenson, a widow, and her daughter Polly at 36 Craven Street near Charing Cross. William, his 27-year-old son, accompanied him to London with two enslaved people. Deborah and their 14-year-old daughter, Sally, remained in Philadelphia.

Benjamin resolved to finish his Poor Richard’s almanac before leaving for London. While at sea in 1757, he wrote a 12-page introduction for the almanac’s final 1758 edition, titled “Father Abraham’s Speech,” eventually known as The Way to Wealth. Father Abraham provides only proverbs on hard effort, thrift, and financial prudence in this intro. The Way to Wealth, along with the Autobiography, was eventually the most commonly reprinted of Benjamin’s publications.

Benjamin’s experience in London at this time was substantially different from his visit from 1724 to 1726. Then, Benjamin was recognized in London, the largest city in Europe and the heart of the rising British Empire, and he met everyone else who was famous, including David Hume, Captain James Cook, Joseph Priestley, and John Pringle, the surgeon to Lord Bute, the king’s top minister.

Benjamin obtained an honorary degree from the University of Saint Andrews in Scotland in 1759, which earned him the title “Dr. Benjamin Franklin.” In 1762, he received another honorary degree from the University of Oxford. Naturally, everyone wanted to paint his portrait and create mezzotints for public sale. Benjamin was fascinated with London and England’s refinement, despising America’s provincialism and ugliness. He was a staunch royalist, bragging about his friendship with Lord Bute, which enabled him to designate his son, William, then 31, as royal governor of New Jersey in 1762.

Benjamin had to return to Pennsylvania reluctantly in 1762 to watch after his post office, but he told his friends in London that he would return soon and even stay forever in England. He had to deal with an uprising of some Scotch-Irish settlers in the Paxton region of western Pennsylvania who were angry at the Quaker assembly’s refusal to finance military protection from the Indians on the frontier after touring the post offices across North America, a trip of 1,780 miles (2,900 km). Benjamin couldn’t wait to return to London after losing an election to the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1764. Deborah remained in Philadelphia, and Benjamin did not see her again.

He was soon confronted with the challenges caused by the Stamp Act of 1765, which sparked a firestorm of criticism in America. Like other colonial agents, Benjamin opposed Parliament’s stamp tax, arguing that taxation should be left to the colonial governments. But, once he realized that the tax was unavoidable, he strove to make the best of a bad situation. After all, he pointed out; empires are expensive. So he obtained the stamp agency for Pennsylvania for his buddy John Hughes and ordered stamps for his printing enterprise in Philadelphia. In the process, he nearly destroyed his reputation in American public life and endangered Hughes’ life.

Benjamin was astounded by the rioters that effectively blocked the Stamp Act from being enforced throughout North America. He advised Hughes to keep his calm in the face of the mob. “A solid Loyalty to the Crown and steadfast Adherence to the Government of this Nation… will always be the wisest course for you and me to adopt, whatever the Madness of the People or their Blind Leaders,” he added. Only Benjamin’s four-hour testimony against the statute before Parliament in 1766 saved his reputation in America. The event shook Benjamin’s earlier belief in the wisdom of British authorities, and doubts and resentments punctuated his earlier confidence. He began to feel his “Americanness” like he had never felt before.

Benjamin spent the next four or five years attempting to bridge the widening chasm between the colonies and the British authority. Between 1765 and 1775, he produced 126 newspaper articles, most of which tried to explain one side to the other. However, as he stated, the English felt he was too American, while the Americans thought he was too English. He had not, however, abandoned his aim to rise through the imperial ranks. However, opposition from Lord Hillsborough, who had recently been appointed head of the new American Department, left Benjamin depressed and disheartened in 1771; in a mood of frustration, nostalgia, and defiance, he began writing his Autobiography, which eventually became one of the most widely read autobiographies ever published.

Benjamin sought to heal his wounds and justify his apparent failure in British politics by telling the first part of his life, up to the age of 25 is the best section of the Autobiography; most critics agree that recounting the first part of his life, up to the age of 25. But, most importantly, in this first section of his Autobiography, he was effectively reminding the World and his son that, as a free man who had established himself as an independent and diligent artisan despite impossible odds, he did not have to kowtow to some patronizing, pampered aristocracy.

When the signals from the British government switched, and Hillsborough was fired from the cabinet, Benjamin abandoned the Autobiography, which he would not continue writing until 1784 in France, following the successful negotiation of the Treaty of Paris securing American independence. Benjamin still believed he could obtain an imperial position and work to keep the empire together. However, he became embroiled in the Hutchinson letters scandal, which finally cost him his job in England.

Benjamin returned to Boston in 1772 with several letters written in the 1760s by Thomas Hutchinson, then lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, in which Hutchinson made some indiscreet remarks regarding the necessity to curtail American liberties. Benjamin foolishly believed that by writing these letters, he would be able to shift blame for the imperial problem to native authorities like Hutchinson and thereby relieve the ministry in London of culpability.

Here Benjamin felt he would allow his ministerial colleagues, such as Lord Dartmouth, to mediate disputes between the mother nation and her colonies with Benjamin’s assistance.

On January 29, 1774, Benjamin stood silent in a theater near Whitehall while being mercilessly insulted by the British solicitor-general in front of the Privy Council and the court, the majority of whom were hooting and laughing. He was fired as deputy postmaster two days later. Finally, in March 1775, he sailed for America after several fruitless attempts at reconciliation.

Although Benjamin was instantly elected to the Second Continental Congress upon his arrival in Philadelphia, numerous Americans remained skeptical of his true loyalties. He’d been gone for so long that some suspected he was a British spy. So he was overjoyed when Congress dispatched him back to Europe in 1776 as the top agent in a delegation seeking military aid and diplomatic recognition from France.

He exploited the French aristocracy’s liberal sympathy for downtrodden Americans to obtain diplomatic recognition for the nascent republic and loan after loan from an increasingly bankrupt French government. His image as the democratic folk genius from the American woods preceded him, and he successfully used it for the American cause.

His image appeared on medallions, snuffboxes, candy boxes, rings, statues, and prints; women even styled their hair in the style of Benjamin. Benjamin nailed his character to a tee. He arrived at the court of Versailles, Europe’s most formal and elaborate court, wearing a basic brown-and-white linen suit, a fur cap, no wig, and no sword, breaking all convention. And the French aristocracy and court embraced it, enamored with the concept of America.

Despite suffering from gout and a kidney stone and being surrounded by spies and his occasionally clumsy fellow commissioners, particularly Arthur Lee of Virginia and John Adams of Massachusetts, who despised and mistrusted him, Benjamin performed magnificently. In 1778, he established military and diplomatic connections with France, and in 1783, he played a critical part in negotiating the final peace accord with Britain. In defiance of their orders and the French alliance, the American peace commissioners negotiated a separate peace treaty with the United Kingdom. It was left to Benjamin to apologize to Louis XVI’s top minister, the Comte de Vergennes, which he did in a wonderfully crafted diplomatic letter.

It’s no surprise that Benjamin’s eight years in France were the happiest of his life. He was doing what he had always wanted to do: influence events on a global scale. In 1784, he continued work on his Autobiography, penning the second portion, which assumes human control over one’s life.

Later life of Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin was forced to come to America to die in 1785, although his friends were in France. Although he was afraid of becoming an “alien in my own country,” he suddenly realized that his destiny was intertwined with America.

His welcome was not fully warm. Family and friends of the Lees in Virginia and the Adamses in Massachusetts spread stories about his adoration for France and debaucherous behavior. The Congress treated him poorly, denying his requests for western property and a diplomatic assignment for his grandson. In 1788, he was reduced to petitioning Congress with a pitiful “Sketch of B. Benjamin’s Services to the United States,” to which Congress never responded. Benjamin replied shortly before his death in 1790 by writing a memorial demanding that Congress abolish slavery in the United States.

This memorandum prompted several members of Congress to launch impassioned defenses of slavery, which Benjamin brilliantly parodied in a newspaper column published a month before his death.

Death

The famous individual died at eighty-four on April 17, 1790, and was buried at the Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia. He learned through experimentation and conversations with others who shared the same interests. Benjamin was an enlightened philosopher interested in all aspects of the natural World.

When Benjamin died, the Senate refused to join the House in designating a month of mourning for him. In contrast to the many professions of French admiration for Benjamin, his fellow Americans only gave him one public eulogy, delivered by his bitter adversary, the Rev. William Smith, who avoided discussing Benjamin’s youth because it appeared awkward.

Benjamin’s youth was no longer embarrassing with the Autobiography publication in 1794. In the decades that followed, he became the idol of numerous early-nineteenth-century artisans and self-made businesspeople looking for an explanation for their success. They were the architects of Benjamin’s modern folkloric image, the man who came to personify the American dream.

A Brilliant Inventor and Scientist’s Legacy

Benjamin was a brilliant inventor and scientist. Lightning rods, glass armonica (a glass instrument, not to be confused with the metal harp), Benjamin stove, bifocal spectacles, and the flexible urinary catheter are some of his well-known inventions. His creations included societal improvements like paying it forward. All of his efforts in the field of science were focused on increasing competency and improving people’s lives. His initiative to hasten news services through his printing plants was one such development.

Benjamin was not only the most famous American of the 18th century but also one of the most famous persons in the Western World of the 18th century; in fact, he is one of the most famous and essential Americans of all time. Although Benjamin is often thought of solely as an inventor, a forerunner of Thomas Edison, his 18th-century popularity sprang not only from his numerous inventions but, more importantly, from his vital contributions to the science of electricity.

Benjamin would have been a contender for the Nobel Prize in Physics if it had been awarded in the 18th century. The fact that he was an American, a plain man from an obscure background who rose from the wilds of America to amaze the entire intellectual World, added to his reputation. Most Europeans conceived of America in the 18th century as a primitive, undeveloped land full of forests and savages, incapable of generating enlightened intellectuals.

Nonetheless, by the mid-18th century, Benjamin’s electrical discoveries had exceeded the achievements of Europe’s most advanced scientists. As a result, Benjamin became a living embodiment of the New World’s inherent untutored intellect, free of the encumbrances of a decadent and exhausted Old World—an image he later used to gain French support for the American Revolution.

Despite his many scientific accomplishments, Benjamin believed that public service was more essential than research, and his political contributions to the foundation of the United States were significant. For example, he created the Articles of Confederation (the first American national constitution). In addition, he was the oldest member of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia, which established the Constitution of the United States of America.

More importantly, as the new American republic’s diplomatic representative in France during the Revolution, he obtained both diplomatic recognition and financial and military aid from the government of Louis XVI, and he was a vital member of the commission that negotiated the treaty under which Great Britain recognized its former 13 colonies as sovereign nations.

Benjamin’s numerous contributions to the comfort and safety of everyday living, particularly in his chosen hometown of Philadelphia. No civic endeavor was too big or too minor for him to be interested in. He invented bifocal glasses, the odometer, and the glass harmonica, in addition to his lightning rod and Benjamin stove (a wood-burning furnace that warmed American households for more than 200 years – armonica). He had theories on everything, from the origins of the Gulf Stream to the common cold.

Matching grants and Daylight Saving Time were two ideas he proposed. As a result, he almost single-handedly contributed to forming a civic society for the people of Philadelphia. Furthermore, he contributed to establishing new institutions, such as a fire department, a library, an insurance company, an academy, and a hospital.

Benjamin’s most important invention was, most likely himself. He established so many characters in his newspaper writings and almanac, as well as in his posthumously published Autobiography, that it’s difficult to determine who he was. Following his death in 1790, he became so identified with the persona of his Autobiography and the Richard maxims of his almanac, for example, “Early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.” He acquired the image of the self-made moralist obsessed with earning and saving money during the nineteenth century.

As a result, many imaginative writers, including Edgar Allan Poe, Henry David Thoreau, Herman Melville, Mark Twain, and D.H. Lawrence, denounced Benjamin as a symbol of America’s middle-class moneymaking corporate principles. Indeed, the famed German sociologist Max Weber regarded Benjamin as the perfect model of the “Protestant ethic” and the modern capitalistic spirit early in the twentieth century. Although Benjamin did become a wealthy tradesman by his early 40s, when he withdrew from his business, he was not known as a self-made businessman or a budding capitalist during his lifetime in the 18th century.

That image was created in the nineteenth century. However, as long as America is portrayed as a nation of entrepreneurship and opportunity, where striving and hard work may lead to success, Benjamin’s image will likely survive.

Sources

- Hornberger, T., & S. Wood, G. (2022, January 13). Benjamin franklin | biography, inventions, books, American Revolution, & facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- Bosco, R. A. (1984). Benjamin Franklin: A Biography.

- Isaacson, W. (2003). Benjamin Franklin: An American Life. Simon and Schuster.

- Lemay, J. L. (2006). The Life of Benjamin Franklin, Volume 1: Journalist, 1706-1730 (Vol. 1). University of Pennsylvania Press.

FACT CHECK: We strive for accuracy and fairness. But if you see something that doesn’t look right, please Contact us.

DISCLOSURE: This Article may contain affiliate links and Sponsored ads, to know more please read our Privacy Policy.

Stay Updated: Follow our WhatsApp Channel and Telegram Channel.