An unfortunate story of a woman who infected hundreds of people with typhoid fever, caused three confirmed deaths, with unconfirmed estimates of as many as 50. She was believed to be the asymptomatic carrier and the spreader of the pathogenic bacteria Salmonella typhi which causes Typhoid Fever. Was she knowingly spreading the disease or was there something else undesirable, what would you call her A Victim or A Killer? Let us know.

Contents

Who was Typhoid Mary?

“Typhoid Mary” is the nickname given to Mary Mallon born in 1869 in Cookstown, County Tyrone, Ireland. In 1884 she left Ireland at the age of 15 and came to the United States for the job. She worked as a maid and lived with her aunt and uncle for a while before going on to work as a cook for elite households.

Sometimes, she lived with the families she worked for, and other times, she stayed with friends in the city, often with one particular male friend unknown. While we’re unsure about her happiness in her personal life, she felt satisfaction and pride in her working life. Many families who hired her praised her cooking skills and caring for children.

Between 1900 and 1907, Mary worked as a cook for eight families in the New York City area. Shockingly, seven of these families got typhoid fever. Her employment in Mamaroneck, New York, in 1900 coincided with locals contracting the disease just two weeks after she started working there. Upon moving to Manhattan in 1901, the family she cooked for began experiencing fevers and diarrhea. When seven out of the eight residents fell ill. Afterward, Mary sought employment with a lawyer but departed when seven out of the eight individuals in that household fell ill.

In June 1904, Mary found employment with wealthy attorney Henry Gilsey. However, shortly after her arrival, four out of the seven servants fell ill. Fortunately, none of Gilsey’s family members, who lived separately, contracted the disease, as the servants had their living quarters. In response to the outbreak, Mary promptly relocated to Tuxedo Park, where she began working for George Kessler. Unfortunately, two weeks later, the household’s laundry woman fell ill with typhoid and was admitted to St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center. Doctors discovered that this was her first encounter with the illness in a long while. Despite the lack of concrete evidence, investigator Dr. R. L. Wilson concluded that the laundry worker was the source of the outbreak. Tragically, the laundry worker passed away not long after.

The relentless pursuit to identify the source of the outbreak or the Patient Zero was still unknown.

The discovery of Typhoid Mary

In the summer of 1906, a woman named Mary Mallon who came from Ireland began her job in Oyster Bay, Long Island, New York as a cook serving the family of Charles Elliot Warren, a prominent New York banker. When the Warren family rented a house of George Thompson in Oyster Bay for the summer of 1906, they took Mary with them. However, what began as a tranquil getaway soon turned ominous when, between August 27 and September 3, six of the 11 family members fell ill with typhoid fever. The sudden outbreak surprised local physicians, who considered the event “unusual” for Oyster Bay. Fearing that his property’s reputation would be tarnished, the landlord George Thompson asked several independent experts to trace the source of the infection. Their detailed investigation extended from water samples from pipes, taps, and toilets to the depths of the sump, yet no trace of typhoid was found.

George Soper and Mary

George Thompson soon sought the help of George Albert Soper II, an American sanitation engineer. Soper also tried to trace the source of the infection in the water samples from pipes, taps, and toilets to the depths of the sump but he failed to find any trace of typhoid. He knew that the disease usually occurred in dirty and unsanitary conditions, so he asked Thompson to give him a list of all the clients, staff, and employees who lived and worked there. Soper looked for any changes in the house that might indicate typhoid. In addition to whether any of the families who stayed there were new to the home at the time of the outbreak. He soon discovered that of all the customers and staff, one person was new to the house at the time of the outbreak, a cook named “Mary Mallon”.

Soper contacted all of Mary’s previous employers and traced her previous employers and found that 22 people had suffered from typhoid while Mary worked for them. Soper began to suspect that it might not just be bad luck that Mary did have the disease, so he began searching for Mary, but it was hard to find her because she usually changed her job as soon as an outbreak began. She used to leave without giving her new address. A few months later in March 1907, when there was an outbreak of typhoid at 688 Park Avenue, New York, he finally found Mary Mallon. The Park Avenue outbreak helped Soper identify Mary as the source of the infection, and with the assistance of the Park Avenue epidemiologist, he came onto the case while it was still open and discovered that here also Mary was working as a cook.

Soper soon visited Mary while she was working at Bownes’ Park Avenue home and told her how she was the reason for all the outbreaks and accused her of spreading the disease. To prove his accusation Soper asked Mary to give the samples of her urine and stool for testing. Mary got angry with Soper saying that she never got sick and refused to give the samples, she also threatened him with a carving fork. Knowing that Mary would not give samples easily, Soper decided to gather a five-year history of Mary’s employment. He discovered that seven out of the eight families who had employed Mary as a cook reported having typhoid. Subsequently, Soper also discovered Mary’s boyfriend’s residence and set up a fresh meeting there. He also took Dr. Raymond Hoobler to get Mary to provide urine and stool samples for examination, once more, Mary refused to give samples, saying that typhoid was widespread and contaminated water and food were to blame for the epidemics not she.

At the time, the concept of asymptomatic carriers was not well understood by medical professionals, and there was not much research and development into bacterial and viral infections and spreading. That’s why no one was ready to believe that they could spread the virus easily, everyone used to argue the same as to why they didn’t get sick earlier.

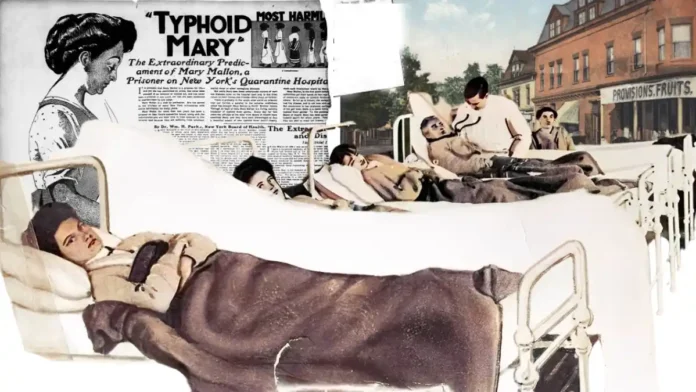

Detention of Mary and Her Media Coverage

This time Soper decided to inform the New York City Health Department, that the department should investigate Mary’s typhoid carrier status. Soon Mary was detained by the Greater New York Charter under sections 1169 and 1170 because she posed a risk to public health. Five police officers and Dr. Josephine Baker forced her into an ambulance. They took Mary to the Willard Parker Hospital, where she was detained and forced to give samples. She was not allowed to get up and use the bathroom on her own for about 4 days.

The investigators found massive numbers of typhoid bacteria in her stool samples, this indicated that the infection source was in her gallbladder. During questioning, Mary admitted that she rarely washed her hands, as we discussed earlier, this was not unusual at the time because the germ theory of any disease still was not fully accepted.

On March 19, 1907, Mary was placed under quarantine on North Brother Island. She provided stool and urine samples three times a week while under quarantine. She declined to have her gallbladder removed, despite the authorities’ suggestion that she did not have the condition. Gallbladder removal was risky back then, and there had been fatalities from the operation. Additionally, Mary refused to give up her career as a cook because she got more money than any other profession. Being without a place to live, she was constantly in danger of going broke.

Following the Journal of the American Medical Association publication of Soper’s research, Mary gained significant media coverage and got the nickname “Typhoid Mary”. She was then referred to as “Typhoid Mary” once more in a textbook that described typhoid illness.

Soper visited Mary when she was in quarantine and told her, he would write a book and give her part of the book-selling royalties. Mary angrily rejected his proposal and locked herself in the bathroom until he left. It’s unclear when she contracted typhoid, as she always denied ever being sick with the disease, and it’s likely she never knew she had it.

Release of Mary and the Second Outbreak

Mary consistently maintained that she never believed she was a carrier of typhoid. With the help of a friend, she sent numerous samples to an independent laboratory in New York for testing, and every result came back negative for typhoid. Even during her time on North Brother Island between March 1907 and June 1909, nearly 25% of her analyses yielded negative results as well.

Eugene H. Porter, the New York State Commissioner of Health, declared after Mary’s 2 years and 11 months of quarantine that disease carriers should not be kept under quarantine and that Mary could be released provided she resigned from her position as cook and made a sincere effort to prevent the spread of typhoid.

On February 19, 1910, Mary said she was “prepared to change her occupation from cook to any other, and would give assurance by affidavit that she would upon her release take such hygienic precautions as would protect those with whom she came in contact, from infection.” She returned to the mainland after she was released from quarantine.

After being freed, Mary was assigned to work in the laundry, where her pay was $20 a month as opposed to $50 when she was a cook. She eventually cut her arm, and it grew infected, preventing her from working for six months. She took a few years off before attempting to cook again. Under pretenses, such as Breshof or Brown, she took cooking employment in defiance of health officials’ direct orders.

Second Outbreak

She worked in a variety of kitchens in restaurants, hotels, and spas over the following five years when no agencies that employed servants for wealthy homes would hire her. Again typhoid epidemics occurred almost everywhere she worked. As soon as Soper learned about the new epidemic, he immediately started looking for Mary, but she was a frequent job changer, and Soper was unable to locate her.

Mary began working at New York’s Sloane Hospital for Women in 1915. Soon, 25 persons were infected with typhoid, and two died. Dr. Edward B. Cragin, the head physician, called Soper and asked him to help with the inquiry. He was already searching for Mary and soon recognized her based on the servants’ vocal accounts and her penmanship.

From here Mary escaped again, but police captured and arrested her when she carried food to a friend on Long Island. Mary was sent back to quarantine on North Brother Island on March 27, 1915. There is less information available about her life during the second quarantine. Authorities kept her on North Brother for over 23 years and provided her with a private one-story cottage. From 1918, she was permitted to make day visits to the mainland. Dr. Alexandra Plavska arrived on the island in 1925 to do her internship. She established a laboratory on the second floor of the chapel and hired Mary as a technician, she used to scrub bottles, make recordings, and prepare glasses for pathologists there.

Death

Mary spent the rest of her life quarantined at Riverside Hospital on North Brother Island. Mary was highly active until she suffered a stroke in 1932, following which she was confined to a hospital. She never fully healed, leaving half of her body incapacitated. On November 11, 1938, she died of pneumonia at the age of 69. Mary’s corpse was cremated and her ashes were interred at Saint Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx. Nine individuals attended the funeral. According to some sources, a post-mortem autopsy revealed viable typhoid bacteria in Mary’s gallbladder. Soper claimed, however, that there was no autopsy, which was used by other scholars to establish a conspiracy to calm public opinion following her death.

Against forcibly quarantining Mary

Not all doctors supported the decision to subject Mary to mandatory quarantine. For example, Milton J. Rosenau and Charles V. Chapin argued that Mary needed education about managing her disease to prevent the spread of typhoid. He believed that isolating her was overly harsh and unnecessary punishment.

Following her arrest and involuntary hospitalization, Mary experienced a nervous breakdown. In 1909, she attempted to sue the New York Health Department, but her case was dismissed by the Supreme Court of New York after her complaint was rejected. In a letter to her attorney, she expressed that she was feeling like a “guinea pig” due to her treatment. Despite suffering from a paralyzed eyelid that required nightly bandaging, she was compelled to provide samples for analysis three times a week. Moreover, she was prohibited from consulting an eye doctor for six months.

Mary underwent intensive medical treatment, which included receiving urotropin in three-month courses for a year. However, this treatment posed a risk to her kidneys. To address this concern, Brewer’s yeast and hexamethylenetetramine were gradually substituted for urotropin, with dosages increasing over time. Initially, Mary was informed that she had typhoid in her intestines. Subsequently, the diagnosis extended to her gut muscles and ultimately to her gallbladder.

During her Quarantine when she hated the nickname “Typhoid Mary” and also wrote in a letter to her lawyer:

“I wonder how the said Dr. William H. Park would like to be insulted and put in the Journal and call him or his wife Typhoid William Park.”

During Mary’s second quarantine, the media changed their minds about her situation. The stories first highlighted Dr. Josephine Baker’s claim that Mary attacked her and the other doctors with forks, fighting, and swearing. Later, press articles moved the responsibility away from her, claiming that she was unaware she was carrying anything and that germs beyond her control were to blame.

According to the newspapers, Mary was not allowed to use the phone to contact anybody other than the surgeons who were treating her and her guard. Stories that originally praised the public health department and the justice system later became sympathetic to Mary and the alleged incidents she witnessed. Public health officials asserted the opposite: she was treated to the best of their abilities but refused to comply with the health officials’ wishes.

Conclusion

Mary Mallon, also known as “Typhoid Mary,” remains a significant figure in the history of public health. Her story reflects the ongoing struggle to balance individual rights with the greater good and to reconcile personal freedoms with the necessity of disease control. In today’s world, as we confront new health challenges, the lessons from Mary’s life take on fresh relevance. They remind us of the importance of prioritizing community health in the face of adversity.

Mary was the first individual discovered to be an asymptomatic carrier of the typhoid pathogen, which left health experts with little to no idea how to deal with her. However, Mary’s case in point assisted these officials in identifying additional persons who had dormant diseases in their bodies, based on the knowledge gained from Mary’s case. Mary’s case sparked debate regarding personal sovereignty and social duty. It was also the first example to provide strong evidence of the presence of asymptomatic carriers.

To this day it’s unclear when she contracted typhoid, as she always denied ever being sick with the disease, and it’s likely she never knew she had it but unknowingly she infected numerous people with the disease while working as a cook in various households in the New York City area.

Mary’s case marked the first time an asymptomatic carrier was detected and forcibly isolated. Her situation has sparked ongoing debate about ethical and legal issues. According to research, Mary infected “at least one hundred and twenty-two people, including five dead”. Other reports connect at least three deaths to Mary’s contact, but the precise number is unknown due to health officials’ failure to get her to cooperate. Some speculate that interaction with her may have resulted in 50 fatalities.

The authors of a 2013 article published in the Journal of Gastroenterology concluded that the story of Mary Mallon, who was declared “unclean” like a leper, may teach us some moral lessons about how to care for the sick and how to avoid illness. By the time she died, New York health officials had found almost 400 other healthy Salmonella typhi carriers, but no one else had been forcibly imprisoned or abused as an “unwanted ill”. This conclusion is based on two scholarly sources, this case underlined the subject’s complexities and the need for a more comprehensive medical and legal-social treatment model aimed at enhancing disease carriers’ status and limiting their influence on society.

However, the ethical implications of her arrest and forced quarantine are still being argued. Historians commonly debate whether Mary was aware that she was infecting people with typhoid due to the regularity with which the disease appeared following her departure. They further argue that antibiotics did not exist at the time and that 10% of individuals infected with Mary died. According to this logic, Mary may be regarded as a murderer of ten percent of people if she knew she was a carrier of the disease, which would justify her incarceration.

On the other hand, others argue that Mary was unaware that she had the bacterium and hence did not deserve to be arrested when she had never committed a crime. At the time, asymptomatic carriers were unknown, and Mary was thought to have stated that she did not feel sick, look unwell, or have any obvious illness. Although Mary did not feel or appear ill, the disease was dormant in what was thought to be her gallbladder.

Also Read:

- Candy Jones: A Secret Agent of CIA Mind-Control Program

- Nina Kulagina: Woman With Ability to Move Objects Using Mind

- Marie Ganz: The Woman Who Threatened Rockefeller

Sources

- Soper, George A. “The Curious Career of Typhoid Mary.” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 15.10 (1939): 698.

- Brooks, Janet. “The sad and tragic life of Typhoid Mary.” CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal 154.6 (1996): 915.

- Adler, Richard; Mara, Elise (2016). Typhoid Fever: A History. McFarland. pp. 137–146. ISBN 978-1-476622095.

- Leavitt, Judith (October 12, 2004). “Typhoid Mary: Villain or Victim?”. PBS Online.

- Walzer Leavitt, Judith (1996). Typhoid Mary: Captive to the Public’s Health. Putnam Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0807021026.

- Job Readiness for Health Professionals: Soft Skills Strategies for Success. Missouri: Elsevier. 2013. p. 189. ISBN 9780323430265.

- Kenny, Kevin (2014). The American Irish: A History. Routledge. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-317-88916-8.

- Job Readiness for Health Professionals: Soft Skills Strategies for Success. Missouri: Elsevier. 2013. p. 189. ISBN 9780323430265.

- Dex; McCaff (August 14, 2000). “Who was Typhoid Mary?”. The Straight Dope.

- Marineli, Filio; Tsoucalas, Gregory; Karamanou, Marianna; Androutsos, George (2013). “Mary Mallon (1869-1938) and the history of typhoid fever”. Annals of Gastroenterology. 26 (2): 132–134. PMC 3959940. PMID 24714738.

- “Dinner With Typhoid Mary” (PDF). FDA. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 21, 2019.

- Soper, George A. (June 15, 1907). “The work of a chronic typhoid germ distributor”. J Am Med Assoc. 48 (24): 2019–22. doi:10.1001/jama.1907.25220500025002d.

- Sammells, Clare A. “Death in the Pot: The Impact of Food Poisoning on History Morton Satin.”

- Rogers, Rosemary (July 31, 2017). “Typhoid Mary: How an Irish cook became the most famous symbol of infectious disease”. Irish America. New York, NY: Irish America Inc.

- Alexander, Caitlind L. (2004). Typhoid Mary: The Story of Mary Mallon: Educational Version. LearningIsland.com. ISBN 9781301357642.

- “In Her Own Words”. NOVA PBS.

- “The Most Dangerous Woman In America”. Nova. Episode 597. October 12, 2004. The event occurs at 28:42-29:52. PBS.

- Walzer Leavitt, Judith; Numbers, Ronald L., eds. (1997). “Typhoid Mary Strikes Back”. Sickness and Health in America: Readings in the History of Medicine and Public Health. Vol. 3. Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299153207.

- “Topics in Chronicling America – Typhoid Mary”. The Library of Congress. October 9, 2014.

- “Food Science Curriculum” (PDF). Illinois State Board of Education. p. 118.

- “Typhoid Mary Is Released”. The Marion Daily Mirror. Marion. February 21, 1910. p. 2.

- Campbell Bartoletti, Susan (2015). Terrible Typhoid Mary: A True Story of the Deadliest Cook in America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-544-31367-5.

- Benenson, Abram S. (1999). “Review of Typhoid Mary”. Journal of Public Health Policy. 20 (3): 375–379. doi:10.2307/3343413. ISSN 0197-5897. JSTOR 3343413. S2CID 189905236.

- Wald, Priscilla (1997). “Cultures and Carriers: “Typhoid Mary” and the Science of Social Control”. Social Text (52/53): 181–214. doi:10.2307/466739. ISSN 0164-2472. JSTOR 466739.

- “‘TYPHOID MARY’ DIES OF A STROKE AT 68; Carrier of Disease, Blamed for 51 Cases and 3 Deaths, but She Was Held Immune Services This Morning Epidemic Is Traced”. The New York Times. November 12, 1938.

- “Typhoid Mary’s tragic tale exposed the health impacts of ‘super-spreaders'”. National Geographic. March 18, 2020.

- Wald, Priscilla (1997). “Cultures and Carriers: “Typhoid Mary” and the Science of Social Control”. Social Text (52/53): 181–214. doi:10.2307/466739. ISSN 0164-2472. JSTOR 466739.

FACT CHECK: We strive for accuracy and fairness. But if you see something that doesn’t look right, please Contact us.

DISCLOSURE: This Article may contain affiliate links and Sponsored ads, to know more please read our Privacy Policy.

Stay Updated: Follow our WhatsApp Channel and Telegram Channel.