When President Mohamed Bazoum’s presidential guard detained him on July 26, 2023, Nigeriens flooded the streets chanting anti-French slogans and waving Russian flags. Across the Sahel, from Mali to Gabon, this type of public endorsement of military takeover has become increasingly common. Slogans suggest a final rejection of neo-colonial overreach. Do these uprisings represent genuine resistance, or are they power grabs masquerading as sweeping rhetoric?

This article interrogates the nature of these coups. Are they honest revolts against colonial legacies, or the latest act in a long-running theater of authoritarian rebranding? We examine the timeline of each upheaval, the historical institutional cracks, the shift in geopolitical patrons, the voices of the embattled citizens, and the outcome on security, rights, and economic stability.

Contents

- 1 Recent Coups Timeline

- 2 The Geography of African Coups

- 3 Colonial Legacies & Weak Institutions

- 4 Anti-Imperialism: Real or Rhetoric?

- 5 Geopolitical Chessboard & New Patrons

- 6 Citizens, Discontent & Coup Cheer

- 7 Outcome of the Coups: Security, Rights & Economics

- 8 Conclusion: Anti-Imperialist Curtain or New Oligarchy?

- 9 Sources

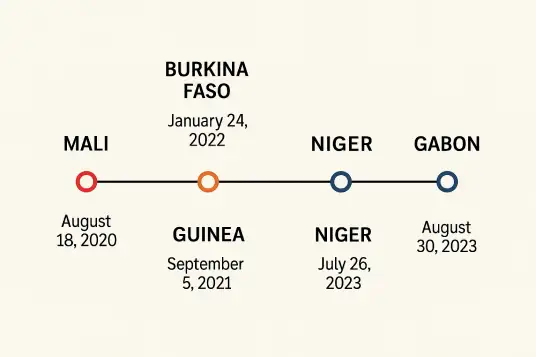

Recent Coups Timeline

In Bamako, Niamey, and Ouagadougou, generals in fatigues proclaim that Africa is “breaking free” from colonial chains. They speak of sovereignty, dignity, and independence, but within weeks, some are signing new security agreements with Moscow or deepening trade with Beijing. The slogans are anti-imperialist; the deals look strikingly familiar.

Mali – August 18, 2020; May 24, 2021

In August 2020, soldiers stormed the Kati military base, detaining President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta amid waves of protest against corruption and unchecked jihadist violence. Colonel Assimi Goïta assumed leadership. In May 2021, he ordered the arrest of the interim president and prime minister for violating the transitional charter, taking over for himself.

Burkina Faso – January 24, 2022; September 30, 2022

Soldiers ousted President Kaboré in January, citing his inability to contain jihadist attacks and widespread corruption. Lt-Col. Damiba promised to restore order, but security deteriorated. After a devastating jihadist attack at Gaskinde in September, Captain Ibrahim Traoré placed Damiba under house arrest on September 30, turning popular discontent into a new power structure.

Niger – July 26, 2023

President Bazoum was detained, and the constitution was suspended by his guard. M62, a pan-Africanist youth movement, played a high-visibility role in protests, chanting “Barkhane Out” and embracing Russian symbols while embracing anti-French rhetoric.

Gabon – August 30, 2023

The Bongo dynasty, in power for more than 50 years, was brought down by a swift military takeover following a disputed election. General Oligui Nguema took over and has surprisingly maintained soft ties with France, which has already scheduled diplomatic re-engagement.

Each coup spoke of popular uprisings rooted in local frustration. But every time, power hardened around generals rather than yielding to democratic renewal.

These leaders are quick to brand their actions as “anti-imperialist,” casting themselves as the heirs of liberation struggles from the 1960s. Yet the reality is messier.

- Mali replaced French troops with the Russian Wagner Group, a shift in patronage, not a break from dependency.

- Burkina Faso canceled some French military accords but quietly sought new arms deals with non-Western suppliers.

- Niger’s junta talks of resisting neocolonialism while maintaining uranium exports vital to foreign markets.

The rhetoric ignites nationalist pride, but it often masks a geopolitical swap, not an emancipation.

The Geography of African Coups

Coup attempts in Africa are not rare. They have been a regular part of political life since independence. Politicians and the media often claim coups have declined since the Cold War, but the numbers tell a different story. Their frequency and success rate have only fallen slightly since 1991. Some areas, like southern Africa, see almost none. Others, especially the Sahel and Central Africa, seem trapped in a cycle of military takeovers. This is not just history repeating itself. It is the result of geography, colonial borders, and fragile power structures that make winning through elections far less certain than seizing power by force.

In the 1960s and 70s, anti-imperialist movements sought to dismantle foreign control of resources, restructure economies, and assert cultural identity. Today’s coups adopt the same slogans but rarely pursue the same systemic changes. Where leaders like Thomas Sankara nationalized industries and invested in local production, many current juntas keep the same extractive contracts intact; they just renegotiate the terms with new partners.

Colonial Legacies & Weak Institutions

These coups did not materialize from nowhere. They were planted in soil made fallow by institutional decay and nepotistic leaks.

The Sahel’s history is deeply shaped by colonial military structures and traumatic nation-building. France left behind fragmented, centralised militaries whose loyalty to civilian institutions was never fully consolidated. Democratic institutions remained fragile, with governance marked by corruption, economic precarity, and security vacuums.

In Mali, the failure of Barkhane, France’s decade-long, multi-thousand-troop counter-terrorism initiative, deepened resentment. It failed to stabilize rural regions and was increasingly seen by populations as a symbol of neo-colonial overreach. And Successive transitional governments could not rally against jihadist advances or public discontent, leading to mass protests and collapse. Operation Barkhane, France’s long counter-insurgency mission, was seen by many as a costly failure and a lingering symbol of neo-colonial presence.

Burkina Faso felt a similar institutional collapse. The Inata massacre, where soldiers died due to logistical neglect, triggered a breakdown in civilian rule. Mali’s eventual shift toward Russia’s Wagner and African Corps was a matter of necessity, not affection, as Western support crumbled.

Similarly, Niger witnessed growing distrust toward Western-backed governments unable to deliver peace or prosperity. That institutional fragility created fertile ground for coups dressed in anti-imperial rhetoric.

This deficiency of civilian legitimacy presented coups as practical solutions in societies starved for security and credible governance.

Anti-Imperialism: Real or Rhetoric?

On the streets, reactions are mixed. In Ouagadougou, crowds cheer anti-French demonstrations, but human rights groups warn of shrinking political freedoms. Nigerian activists caution that foreign flags, whether tricolor or tricolor with a different emblem, still represent foreign leverage. Afrobarometer surveys suggest many citizens welcome the removal of unpopular leaders but remain skeptical that juntas will deliver better governance or true independence.

In Niger, coup leaders used strong anti-French slogans as a shield. The M62 Movement, inspired by pan-African and anti-imperialist ideas, organized large protests shouting “Barkhane out,” “Down with France,” and “Long live Putin,” while waving Nigerien and Russian flags. In Burkina Faso, Gen. Traoré relied heavily on the image of revolutionary leader Thomas Sankara and banned French troops, promoting a story of national freedom.

In Mali, Goïta’s military government openly used anti-French messages to justify deals with Wagner, a Russian private military company. Wagner’s arrival pushed out French influence and was promoted as a way to restore Mali’s independence, not as foreign meddling. Russian propaganda supported this by painting Western nations as colonial powers and Russia as a friend to post-colonial states.

Wagner’s actions in Mali included violent raids like the one in Moura, where many civilians, especially from the Peul community, were allegedly killed or tortured. While these operations weakened jihadist strongholds, they also created fear and deepened ethnic tensions. The outcome was clear: one foreign power left, and another – more brutal – took its place.

Real or Rhetoric?

Coups often appear as liberation movements, but a closer look reveals symbolism overtaking substance. In Niger, M62 made the coup appear part of an anti-imperial uprising, chanting Russia-friendly slogans while hurling France from the stage. In Burkina, Traoré resurrected Sankara’s avatar to frame his rule as a second independence moment.

Mali touted the departure of France as symbolic liberation while welcoming Wagner and, later, an official Russian presence. What they gained was not sovereignty but security dependence.

Yet real consequences accompanied the rhetoric. Mali saw civilian abuses increase under foreign mercenaries. In Burkina, Traoré’s campaigns were marked by violence against civilians, such as the 2023 Zaongo massacre, where women and children were among the casualties. Freedoms cracked across these states; media shrunk and NGOs came under threat.

Anti-colonial slogans may inspire, but they can serve as props rather than portals to genuine autonomy.

Geopolitical Chessboard & New Patrons

With Western aid and attention shifting elsewhere, new powers moved in. Russia, via the Africa Corps, offered stability. Media, weapons, and training filled the void left by the faltering partnerships of old. The result was a new geopolitical map where the strings of influence are less visible but just as binding.

Regional bodies such as ECOWAS and the African Union responded with condemnations and sanctions against Niger or Mali. But their influence flagged, unable to reverse changes already entrenched. In Gabon, where France retained economic leverage, dialogue resumed quickly, proving that patronage still works when resources matter. China may quietly be positioning itself as a stabilizer via energy deals.

In effect, these states traded one external master for another, under the guise of liberation.

Citizens, Discontent & Coup Cheer

Popular endorsement of coups is less ideology than desperation. In capitals like Niamey and Bamako, protesters cheered soldiers because democratic institutions had stopped delivering. The result was a longing for control at any cost.

In Niger, Bazoum remains under house arrest months after the coup. Local media and justice systems stopped functioning with normal oversight. International focus waned amid new crises. The consequences for political and civic rights were immediate and severe.

In Burkina Faso, growing security operations harmed civilians more than they delivered safety. Blood on the streets became the cost of the new order.

Coup support may tell citizens what they want. But it rarely delivers what they need.

Outcome of the Coups: Security, Rights & Economics

Security

Far from resolving instability, violence escalated. Sahel insurgents tempered tactics with drones and organized crime. Conflict zones expanded, never contracted.

Human Rights

In Mali, Wagner-linked units left a trail of civilian deaths and torture. In Burkina, security forces were accused of massacring civilians. Press and civil society came under tight control.

Economy

Sanctions and international isolation pushed economies into hardship. Gabon’s relative openness allowed few international companies to stay, showing how dependency still defines governance options.

Public confidence did not return with the coups. If anything, they eroded trust in institutions even further.

Conclusion: Anti-Imperialist Curtain or New Oligarchy?

The recent coups are painted as anti-imperialist uprisings wearing anti-imperialist rhetoric like armor, grounded in popular grief and historical injustice. But underneath, they are disciplinary regimes with new allegiances and old patterns.

Beneath the slogans lies a shifting game: Western influence replaced by new patrons, often struggling states replaced by militarized regimes. Genuine dissatisfaction with neo-colonial power exists, yet the military solutions have not delivered on the promise of stability or sovereignty. Instead, power has been consolidated into narrower hands, human rights declines have deepened, and new dependencies have been forged. In simple terms, they replaced one form of external leverage with another. They traded popular legitimacy for militarized rebranding.

True decolonization requires institutional strengthening, inclusion, and accountability, not just replacing one dominance with another. These coups, for all their anti-imperial rhetoric, may have ushered in a new era of sovereignty only to exchange one set of guardians for another.

True liberation requires rebuilding trust, institutions, and civil society, not changing uniforms. Sovereignty must be more than a slogan. It must be institutionalized, inclusive, and rights-based.

Power taken at gunpoint rarely builds a durable peace. It delivers authoritarianism, often with new external backers. Africa’s future depends on governance from below, not from above.

These uprisings are not silent because they lack noise; they are silent because they rarely speak the full truth. Behind the anti-imperialist speeches lies a pattern of strategic realignment, where one sphere of influence is traded for another. Until coups deliver structural change that empowers citizens rather than reshuffles foreign patrons, Africa’s so-called liberation wave will remain more about geopolitics than genuine independence.

Sources

- Smith, Stephen. “Macron’s Mess in the Sahel: How a Failed French Mission Gave Russia New Sway in Africa.” Foreign Affairs, 11 Mar. 2025.

- “2020 Malian Coup d’état.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

- “Timeline: What Happened in Mali since a Military Coup in August.” Al Jazeera, 25 May 2021.

- “January 2022 Burkina Faso Coup d’état.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

- “What Caused the Coup in Burkina Faso?” ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies, 2022.

- “2022 Gaskindé Attack.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

- “Spotlight | Understanding Burkina Faso’s Latest Coup.” Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

- “2023 Nigerien Coup d’état.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

- “Niger: President Bazoum and His Wife Remain Detained amid a Growing and Incomprehensible Indifference.” Le Monde, 16 Sept. 2024.

- “2023 Gabonese Coup d’état.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

- “France, Gabon: General Oligui Nguema a ‘Putschist Friend’ in Paris.” Le Monde, 28 May 2024.

- “2020 Malian Protests.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

- Pilling, David. “After the Coup: What Happens Next in Mali?” TIME, 27 Aug. 2020.

- “History of Mali.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

- “Zaongo Massacre: Burkina Faso Crisis Continues to Spiral.” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2023–2025.

- “Traoré’s Regime Marks a Dangerous Turn in Burkina Faso.” Springer Link, 2025.

- “Human Rights Abuses by Security Forces in Burkina Faso.” AP News, 1 Feb. 2023.

FACT CHECK: We strive for accuracy and fairness. But if you see something that doesn’t look right, please Contact us.

DISCLOSURE: This Article may contain affiliate links and Sponsored ads, to know more please read our Privacy Policy.

Stay Updated: Follow our WhatsApp Channel and Telegram Channel.